2.

Please provide your organization’s comments to the issues raised on scarcity pricing enhancements and feedback the CAISO should consider in preparation for the straw proposal.

- The CAISO should balance the use of scarcity price incentive payments with the use of new and existing penalty tools.

In this Price Formation Enhancements (PFE) initiative, the CAISO will consider scarcity pricing changes to improve real-time market price incentives during periods of tight supply conditions.[1] Scarcity pricing is a market tool that sets special prices for energy, ancillary services, and ramping products when supply of those products is insufficient to meet demand, namely during a power balance constraint violation.[2] The CAISO states that scarcity prices are important to attract supply and reduce demand during tight system conditions and also to incentivize resources to be available and perform.[3]

Scarcity pricing adjusts the clearing price of energy paid to generators, which is ultimately borne by ratepayers. When scarcity pricing occurs, the real-time market (RTM) price of energy can increase. This increase can penalize generators who fail to deliver energy if they were committed in the day-ahead market (DAM) since those generators are typically charged the real-time price of energy for the volume of undelivered energy. However, energy that is scheduled in the RTM that successfully delivers is paid the scarcity price, which typically is above the usual locational marginal price (LMP) of energy used during normal power balance constraint conditions.

Since the CAISO intends to use scarcity pricing to incentivize resources to be available and perform, the PFE initiative should also consider options to properly penalize resources that fail to meet delivery obligations. Scarcity pricing must exceed the DAM price to effectively penalize non-deliveries scheduled in the DAM that are charged the RTM price. The CAISO should explain exactly when a DAM-scheduled resource would face costs for non-delivery, and should determine the necessary price spread between the DAM price and RTM scarcity pricing that would effectively incentivize generators to deliver committed energy. In order for the CAISO and stakeholders to develop efficient solutions, the CAISO should also clarify if bid cost recovery may in some instances prevent this type of buy-back penalty.[4]

The CAISO should also explore other types of penalties for non-deliveries to ensure scheduled resources actually deliver. At the June 9, 2022, stakeholder meeting, the CAISO and CPUC’s Energy Division also discussed that certain imports may not be liable to pay the buy-back penalty at real-time prices if those import resources fail to deliver.[5] The CAISO should explain in its next proposal how certain imports may not be subject to penalties for non-delivery, including any factors that may weaken the effectiveness of existing penalties like the Uninstructed Deviation Penalty.[6] Existing penalties or lack of penalties for undelivered commitments should be enhanced or developed in this initiative in order to incentivize successful deliveries and help mitigate the use of scarcity pricing.

- The RAAIM should be enhanced to appropriately penalize RA resources that fail to deliver.

Scarcity pricing would likely occur when available supply is insufficient to meet demand. The CPUC’s RA program establishes resource obligations to make all necessary supply available to the CAISO. The CAISO maintains the RAAIM in part to penalize RA resources for failing to make themselves available to and deliver to the CAISO.[7] The Department of Market Monitoring has stated that the RAAIM as currently designed “provides fairly weak incentives for resources to be available and perform.”[8] Contracted RA resources are either owned by LSEs or contracted by LSEs to be available to the CAISO according to RA obligations. Failing to effectively penalize RA resources for reneging their obligations threatens reliability and enables a resource to collect unearned capacity payments.

The CAISO should, either in this or another initiative, enhance the RAAIM to strengthen the penalties for non-delivery of RA resources. The purpose of the RA fleet is to create sufficient supply to meet reliability events, and that purpose is undone if RA resources fail to deliver. At this time, Cal Advocates does not offer a proposal for how to best enhance RAAIM but one step in the right direction would be to increase the RAAIM Price from $3.79 per kilowatt-month to a rate that better reflects the value of capacity during scarce conditions.[9]

- If the CAISO adopts scarcity pricing, its use should be limited to the period beginning when CAISO initiates load shedding and ending when the CAISO cancels load shedding, or IOUs begin to restore load, whichever is earlier.

The CAISO has outlined two categories of concerns that are scoped into the scarcity pricing component of the PFE initiative: inappropriate incentives for market participants during tight system conditions, and pricing during ancillary services shortages.[10] Discussion during the July 12, 2022 workshop suggested that the CAISO is open to making changes to the demand curve for the Flexible Ramping Product (FRP) to increase its bid cap and provide an earlier price signal that ancillary services may be approaching scarcity.[11] The CAISO should clarify if it intends to consider raising the bid cap beyond $2000 per megawatt-hour (MWh) for scarcity pricing, or if it intends to prevent prices from collapsing during a load shedding event. Cal Advocates opposes raising the bid cap to another, higher level because raising the bid cap is unlikely to solve the bidder incentive problems. Moreover, raising the bid cap would simply relocate the same challenges to a higher price level and thereby increase ratepayer costs.

If the CAISO does adopt scarcity pricing in some form, it will need to determine an appropriate trigger mechanism. Intuitively, ongoing load shedding might seem to be a useful trigger. However, load shedding is an inherently lumpy process in terms of capacity and time. For example, during the August 14, 2020 load shedding events, the CAISO ordered two phases of 500 MW load shedding for a total of one hour.[12] However, PG&E failed to comply with the one hour load shedding timeline and exposed their customers to outages lasting up to 2.5 hours,[13] and PG&E’s load was not fully restored until 30 minutes after the CAISO canceled the Stage 3 Emergency.[14] If scarcity pricing were tied to load shedding, CAISO ratepayers would have been exposed to excess prices for a full 30 minutes longer than if CAISO had declared a Stage 3 Emergency. This exposure effect would have been even more egregious on August 15, 2020, when the Stage 3 Emergency lasted 20 minutes but PG&E shed load for a full 90 minutes.[15] Tying scarcity pricing to load shedding would have resulted in 70 superfluous minutes of costs to ratepayers on August 15, 2020.

Beyond the temporal problems of tying scarcity pricing to load shedding, the amount of load shed also poses challenges to attributing the downstream costs for scarcity pricing. Notably, while the IOUs responded with a total of 1,072 MW load shed on August 14, 2020, the FRCA notes that “some of the smaller [utility distribution companies] failed to respond”[16] and that “[s]elected non-CPUC jurisdictional entities…stated that they did not shed load on either day.”[17] It is possible that the non-participation of non-CPUC jurisdictional entities led to extended load shedding events because these entities failed to respond to CAISO orders. This failure would violate cost causation principles by exposing CAISO ratepayers to longer periods of high prices that could have been ameliorated if all entities shed load according to their obligations.

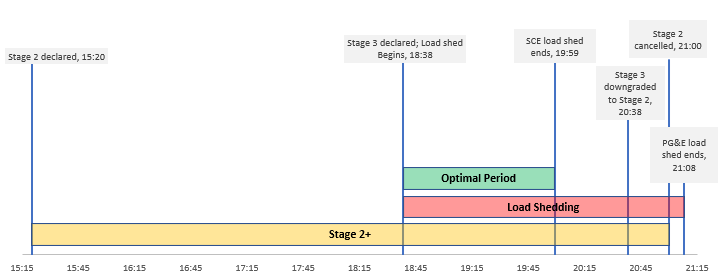

Alternatively, scarcity pricing could be tied to the CAISO issuing an Energy Emergency Alert (EEA) 3. However, the EEA3 comprises actions undertaken in the CAISO’s former Stage 2 and Stage 3 emergencies.[18] For example, the CAISO’s EEA3 procedure calls for steps to avoid load shed, such as “procuring Legacy RMR and any other available Out-of-Market Operating Reserve.”[19] If these actions are successful, they can avoid the need for the CAISO to call for load shedding. Another problem with tying scarcity pricing to the EEA3 is that if an EEA3 is initiated under the same conditions as Stage 2 emergencies, scarcity pricing would likely begin prior to load shedding and could end long after load shedding. The timing of Stage 2 and 3 emergencies on August 14, 2020 demonstrates this problem. Figure 1 shows a timeline of events on August 14, 2020. The CAISO declared a Stage 2 emergency at 3:20 pm (yellow box), upgraded to Stage 3 at 6:58 pm (initiating load shedding, the red box), downgraded to a Stage 2 at 8:38 pm, and cancelled the Stage 2 emergency altogether at 9:00 pm. If the CAISO’s EEA3 is in fact triggered by the same contingencies as a former Stage 2 emergency, and scarcity pricing were tied to the EEA3, ratepayers would have faced almost six hours of elevated prices, which is untenable.

Figure 1: August 14, 2020 Emergency Stages and Load Shedding Timeline

Focusing on the August 14, 2020 example, the optimal time period when scarcity pricing could have had utility for the CAISO was the period from when the CAISO began to shed load (6:38 pm) until the time when load began to be restored (7:59 pm, green box). Artificially maintaining prices at the bid cap would not have helped prior to the declaration of the Stage 3 emergency because the Real-Time Market and Fifteen Minute Market had already been at or around the bid cap for about 40 minutes, sending a clear and obvious price signal.[20] Conversely, the market settling prices did not increase in the interval immediately after SCE began to restore load at 7:59 pm, indicating that the load shedding was adequate for restoring the CAISO’s operating reserves above the 6% threshold.[21] It would not be rational to continue scarcity pricing when CAISO entities are able to successfully begin restoring load, even if the CAISO has not yet downgraded its emergency status.

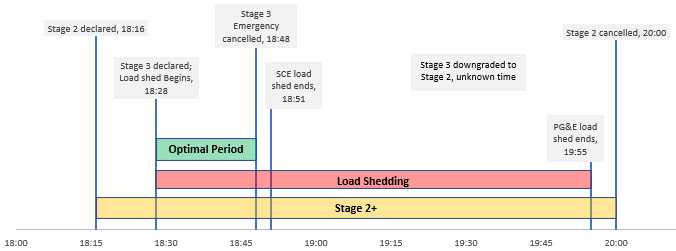

The events of August 15, 2020 yielded a slightly different scenario for determining when to end a scarcity pricing event. Figure 2 illustrates the timeline of CAISO emergency stages and load shedding. On August 15, 2020, the CAISO cancelled its Stage 3 Emergency at 6:48 pm, three minutes prior to the IOUs beginning to restore load at 6:51 pm.[22] In this scenario, the period when a form of scarcity pricing might be useful for attracting external bids was from the start of load shedding to the time when the CAISO cancelled load shedding (green box).

Figure 2: August 15, 2020 Emergency Stages and Load Shedding Timeline

In summary, if the CAISO is considering utilizing scarcity pricing to attract external generation, any mechanism that artificially maintains bid prices at the bid cap should be targeted precisely and limited to the period that begins when the CAISO initiates load shedding and ends either when the IOUs begin to restore load (as on August 14, 2020) or when the CAISO cancels load shedding (as on August 15, 2020), whichever occurs first. None of these conditions map neatly onto the EEA levels that the CAISO now uses to guide system emergencies.

[1] CAISO, Price Formation Enhancements Issue Paper, July 5, 2022 (Issue Paper), p. 3.

[2] The power balance constraint is the normal operating and pricing conditions of the integrated forward market and real-time market which allows the marginal price of supply (generation) to clear at a level that provides sufficient energy and/or ancillary service products to meet demand. If the power balance constraint system is unable to procure sufficient supply, a power balance constraint violation occurs and the CAISO will use other tools, including scarcity pricing, to modify load and/or increase generation. See also CAISO Tariff Appendix C, Section C.

[3] Issue Paper, p. 3. See also, Issue Paper, p. 7 (“Penalty prices should be sufficiently high to incentivize performance of scheduled resources and induce availability of resources (including imports) to the maximum extent possible.”)

[4] The CAISO describes that in some instances bid cost recovery can be made if a DAM schedule is found to be infeasible in the RTM. State of charge requirements for energy storage resources may be one legitimate instance of infeasibility, but it is unclear if bid cost recovery is being appropriately applied in other instances if a DAM commitment fails to deliver. Issue Paper, p. 19.

[5] Price Formation Enhancements Stakeholder Workshop at 0:14:29, June 9, 2022 (Workshop Video), available at: https://youtu.be/dOap2rQvihY?t=869.

[6] Uninstructed Deviation Penalties apply costs to deliveries that deviate from CAISO schedules. Negative deviations are charged 50% of the real-time LMP. CAISO BPM CC4470 Version 5.0, available at: http://www.caiso.com/Documents/February29_2008Amendment-Tariff-ImplementCharge_UndeliveredImportorExportBidsinDocketNo_ER08-628-000.pdf. See also CAISO Tariff 11.23.

[7] RAAIM also makes incentive payments if an RA resource performs well or above its commitment. CAISO Tariff 40.9.6(b).

[8] CAISO Department of Market Monitoring, Comments on Resource Adequacy Enhancements Sixth Revised Straw Proposal – Phase 2A, February 1, 2021, p. 3, available at: http://www.caiso.com/Documents/DMMCommentsonResourceAdequacyEnhancements-SixthRevisedStrawProposal-Feb12021.pdf.

[9] The RAAIM Price is currently set at 60% of the CPM Soft-Cap Price of $6.31/kW-mo. CAISO Tariff 40.9.6.1.

[10] Issue Paper, pp. 11-13.

[11] Workshop Video at 0:34:00, available at: https://youtu.be/dOap2rQvihY?t=2040.

[12] CAISO, CPUC, and the California Energy Commission, Final Root Cause Analysis: Mid-August Extreme Heat Wave (FRCA), January 31, 2021, p. 34.

[13] PG&E load shedding on August 14, 2020 lasted from 6:38 pm until 9:08 pm. FRCA, p. 35.

[14] CAISO downgraded the Emergency from Stage 3 to Stage 2 at 8:38 pm on August 14, 2020. FRCA, p. 29.

[15] FRCA, p. 35.

[16] FRCA, p. 36.

[17] FRCA, p. 35.

[18] CAISO, AWE to NERC EEA Training, April 20, 2022, p. 12, available at: https://www.caiso.com/Documents/Presentation-AWE-NERC-EEA-Training-Apr20-2022.pdf.

[19] CAISO Operating Procedure No. 4420, System Emergency, version 14.0, May 1, 2022, p. 13.

[20] Issue Paper, p. 8.

[21] Issue Paper, p. 8.

[22] Once again, PG&E was unable to restore load until much later at 7:55 pm.

3.

Please provide your organization’s comments to the issues raised on fast-start pricing and feedback the CAISO should consider in preparation for the straw proposal.

The CAISO states that it believes it is appropriate to reconsider fast-start pricing “[a]s the ISO and other entities explore broader regional market participation.”[1] This connects the fast-start pricing reconsideration to the ongoing EDAM Initiative, which would integrate several external balancing area authorities into a larger market. However, CAISO staff also suggested that the CAISO believes that fast-start pricing is supportable on its own merits,[2] although the CAISO has historically expressed concern over fast-start pricing.[3] In its next proposal, the CAISO should explain why it believes fast-start pricing would be more economically efficient under EDAM than under the current market structure. Additionally, Cal Advocates agrees with the CPUC Energy Division’s observation that if fast-start pricing is a prerequisite for EDAM, then the benefits and costs of fast-start pricing should be considered holistically in assessing whether EDAM provides net benefits to CAISO ratepayers.[4]

Finally, any proposal to implement fast start pricing must consider how to address the interaction with CAISO LSEs’ current long-term capacity contracting. A substantial share of RA is subject to Integrated Resource Plan or Renewable Portfolio Standard contracts with terms of 10-year terms (or longer),[5] and LSEs will be unable to renegotiate contract costs for the foreseeable future. During the PFE workshop, the CAISO dismissed the link between capacity contract pricing and market revenues, suggesting that capacity payments should cover suppliers’ going-forward fixed costs.[6] This is empirically a stale assumption. The average price of RA capacity reported by CPUC-jurisdictional LSEs in 2020 was $4.97/kW-mo,[7] which far exceeds the Annual Technology Baseline estimate for the going forward fixed costs of a combined cycle thermal resource in 2020 at $2.25/kW-mo.[8] Likewise, this heuristic assumption about capacity pricing is out of step with the historically exceptional circumstances and prices shaping the current RA capacity market. The CPUC recently updated stakeholders on Summer and Midterm Reliability resource procurement, noting heretofore-unseen supply chain challenges such as manufacturing disruptions, shipping disruptions, market-tightening and intense competition with other markets, wide-ranging materials shortages, and commodity market challenges.[9] Additional factors include the CAISO’s Interconnection Supercluster 14, which is extending deadlines and causing delays.[10] The long-term implications of the current RA capacity market are not part of a recurring pattern of objections. Where bidders have leverage due to the ongoing tightness of the capacity market, the competitiveness of a bidder’s bid increasingly turns on the bidder’s ability to translate estimated market revenues into bid discounts, even as the bid remains above true going-forward costs.

[1] Issue Paper, p. 13; see also Workshop Video at 48:37, available at: https://youtu.be/dOap2rQvihY?t=2917.

[2] Workshop Video at 1:12:40, available at: https://youtu.be/dOap2rQvihY?t=4360.

[3] Issue Paper, p. 14.

[4] Workshop Video at 1:22:00, available at: https://youtu.be/dOap2rQvihY?t=4920.

[5] See CPUC Decision (D.) 19-11-016, Decision Requiring Electric System Reliability Procurement for 2021-2023, November 7, 2019; issued in Rulemaking (R.) 16-02-007; and CPUC D.21-06-035, Decision Requiring Procurement to Address Mid-Term Reliability [2023-2026]), June 24, 2021; issued in R.20-05-003.

[6] Workshop Video at 1:16:40, available at: https://youtu.be/dOap2rQvihY?t=4600.

[7] CPUC, 2020 Resource Adequacy Report, April 2022, p. 24, available at: https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cpuc-website/divisions/energy-division/documents/resource-adequacy-homepage/2020_ra_report-revised.pdf.

[8] National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Corrected 2021 Annual Technology Baseline (ATB), August 12, 2021, “Natural Gas_FE” tab, retrieved from https://data.openei.org/submissions/4129.

[9] CPUC, Tracking Energy Development: Presentation at CEC Staff Workshop on Summer and Midterm Reliability, May 20, 2022, p. 5, available at: https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cpuc-website/divisions/energy-division/documents/summer-2021-reliability/tracking-energy-development/cec-may-reliability-workshop-tracking-energy-development-may-2022.pdf.

[10] CPUC, Tracking Energy Development: Presentation at CEC Staff Workshop on Summer and Midterm Reliability, May 20, 2022, p. 5, available at: https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cpuc-website/divisions/energy-division/documents/summer-2021-reliability/tracking-energy-development/cec-may-reliability-workshop-tracking-energy-development-may-2022.pdf.

4.

Please provide your organization’s comments to the issues raised on the real-time market’s multi-interval optimization, focusing on interaction with energy storage resources, and related changes to real-time bid cost recovery, and feedback the CAISO should consider in preparation for the straw proposal.

The CAISO seeks stakeholder input on proposed solutions to revise the MIO used in the real-time dispatch (RTD) market.[1] Stakeholders claim that the MIO leads to un-economic dispatches in the RTD due to short-term forecast uncertainties.[2]

Stakeholder suggestions include:

- Eliminate the MIO.

- Remove storage resources from the MIO.

- Place more weight on early advisory intervals than later advisory intervals.

- Award resources bid cost recovery (BCR) so that the resource owner is made financially whole in the real-time market if it the resource is dispatched uneconomically in real-time.

Cal Advocates recommends:

The CAISO should not eliminate the MIO. The MIO is the primary tool used to position all resources to meet load in the real-time market under dynamic conditions by incorporating short-term system information that is not available in either the day-ahead or fifteen-minute markets.[3] If the MIO is eliminated, operators would need to rely more heavily on exceptional dispatch (ED), which is not optimized, but rather issued in response to quickly changing conditions based on operator experience. More frequent ED is likely to lead to a similar or greater level of un-economic dispatches for energy storage resources.

Storage resources should not be removed or be allowed to opt-out from the MIO. As energy storage resources become a significant component of the CAISO fleet, storage will increasingly be needed to maintain system reliability. If the MIO has visibility into only a part of the overall fleet, other resources such as gas units may be dispatched in real-time in place of storage to meet dynamic system conditions. Such outcomes would lead to greater costs and greenhouse gas emissions.

The CAISO should further examine advisory interval weighting in the MIO. The MIO dispatches resources in the next 5-minute interval (the binding interval) based upon forecasted prices in the subsequent 12 5-minute intervals (the advisory intervals.) Stakeholders suggest that more weight should be placed on early rather than later advisory intervals because of greater price uncertainties in the later intervals.[4] At the October 1, 2021, Market Surveillance Committee meeting, committee member Scott Harvey indicated that other ISOs use various methodologies to place more weight on earlier system price forecasts, but that the methodologies were largely heuristic, not sophisticated, and could lead to other unanticipated and detrimental outcomes.[5] The CAISO should conduct rigorous testing of alternative weighting schemes using historical market data and should investigate both positive and negative effects on economic dispatch for individual resources, as well as impacts on system cost and reliability.

Any revisions to BCR should comprehensively evaluate changes for all resources, and not be implemented in isolation for specific resource types. The CAISO should not adopt specific bid cost recovery modifications targeted at compensating energy storage for uneconomic dispatches in the MIO over just 12 five-minute intervals. The CAISO should only modify BCR to achieve overall efficient market outcomes, while assuring that ratepayers do not inordinately bear the costs of BCR.

If BCR is implemented for uneconomic dispatch in the MIO for storage, Cal Advocates recommends that the resources be required to pay back gains from MIO dispatches. Payments back to the CAISO should be calculated using the same counterfactual scenarios used in calculating BCR compensation to the resources.

[1] Issue Paper, p. 3.

[2] Issue Paper, p. 16.

[3] Issue Paper, pp. 16-17.

[4] Issue Paper, p. 16.

[5] Market Surveillance Committee Meeting General Session, October 1, 2021, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Jg6M7r5FK4.