1.

Please provide a summary of your organization’s comments on the WEIM Resource Sufficiency Evaluation Enhancements Phase 2 straw proposal and July 11, 2022 stakeholder call discussion:

The purpose of the resource sufficiency evaluation (RSE) test is to ensure that CAISO and other Western Energy Imbalance Market (WEIM) participants have sufficient resources to meet load before the transfers occur in the energy imbalance market itself – that is, among other reasons, that no entity is leaning.

In the past year, the CAISO has identified and discussed a number of issues associated with the RSE, two of which are critically important to CPUC jurisdictional load serving entities and their customers. First, CAISO has identified that CAISO’s markets clear exports based on advisory WEIM transfers, but that these advisory WEIM transfers are not included in the RSE test itself, even though the exports that cleared the market as a result of the advisory WEIM transfers are included in the test. Thus, CAISO’s markets could clear exports based on the expected WEIM transfers and then fail the RSE when these WEIM transfers are not included in the test itself.[1] Second, CAISO has identified that it clears exports in the hour ahead scheduling process (HASP), based on imports that are bid into the HASP process, but that these HASP imports are not financially binding. This presents a reliability issue to CAISO customers if CAISO supports these cleared exports and the non-financially binding HASP imports do not materialize.

In its issue paper, CAISO proposes to address these two issues in the following manner. First, CAISO proposes that it will include in the RSE only those exports that are identified as high priority exports or that CAISO has a reasonable expectation can be supported by resources internal to CAISO.[2] Second, CAISO proposes that HASP exports with high priority will be given priority equal to load, but that low priority exports will be tagged as “firm-provisional” and that it would curtail these exports, if necessary, to maintain reliability. However, CAISO indicates that it would “only look to curtail these LPT exports to the extent contingency reserves have been deployed and were unable to be recovered, or an event outside of existing planning criteria occurs wherein the CAISO is unable to meet its internal demand through the exercise of its reserves.” Further, CAISO clarifies that its default would be to not curtail exports to a BAA in an EEA-2 (“with the default being to exclude curtailments into BAAs that have entered into an EEA-2”).

Separate from these issues and CAISO’s proposed solutions, stakeholders requested CAISO consider financial penalties for RSE failures, rather than limiting transfers to the last feasible schedule. In this issue paper, CAISO proposes to allow WEIM entities that fail the RSE, to cure the resource insufficiency through a hurdle rate priced at the bid cap (i.e., either $1,000/MWh or $2,000/MWh, depending on cost verified bids above the soft bid cap).

CPUC staff broadly supports CAISO’s efforts to address these issues and appreciates CAISO explanations, proposed solutions, and creative thinking, but CPUC staff has a number of questions about how CAISO proposals will work in practice, which are discussed in further detail below.

- CPUC staff supports CAISO’s proposal to include in the RSE only those exports that are identified as high priority exports or that CAISO has a reasonable expectation can be supported by resources internal to CAISO, but staff has number of questions about how this will work in practice.

CPUC staff would appreciate it if CAISO staff could walk through numerical examples of how this would work and how this will be shown in OASIS. For example, if CAISO has 45,000 MW of load and 45,000 MW of resources, but then has 1,000 MW of HASP imports and 1,000 MW of anticipated WEIM transfers, and as a result clears 2,000 MW of exports, CPUC staff assumes that the CAISO footprint would pass the RSE (45,000 MW of resources and 45,000 MW of load and no exports would be included in the test). It would be helpful if CAISO could clarify that this understanding is correct.

A more complicated example might include consideration of resource adequacy imports. Assuming the same fact set above, but CAISO had 1,000 MW of RA imports rather than HASP imports, is CPUC staff’s understanding correct that as with the previous example, the CAISO footprint would pass the RSE and the exports would not be counted in the RSE since they are not supported by “resources internal to the CAISO”?

In addition, would CAISO’s OASIS show the net interchange with or without the non-supported exports? Or would both be included in the OASIS functionality?

Finally, it would be helpful if CAISO could confirm that failure of imports to tag at T-40 would likely have no effect on whether the CAISO footprint passes or fails the RSE, primarily because during stressed system conditions (which is when CAISO might fail to pass the RSE), any unsupported exports would not be included in the test to begin with.

Using the same example as above to clarify CPUC staff’s understanding of this scenario, with 45,000 MW of load and resources, 1,000 MW of HASP imports and 1,000 MW of WEIM transfers supporting 2,000 MW of exports, is staff’s understanding correct that it would likely be irrelevant whether the HASP imports failed to tag at T-40 for purposes of the RSE? If this is not correct, it would be helpful if CAISO could explain why this would not be the case. The only circumstance that CPUC staff could see it mattering for the CAISO footprint itself is if the HASP/other imports were necessary to support CAISO load and these imports failed to tag at T-40.

- CPUC staff has a number of questions about CAISO’s proposal to create a new category of “firm-provisional” imports that would be curtailed to ensure reliability, if necessary.

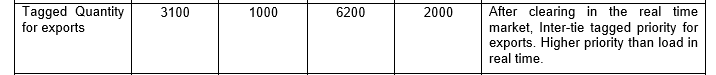

First, in the issue paper, CAISO indicates that it currently has tariff authority to curtail low priority exports (“under its existing tariff authority retains the ability to curtail lower priority exports to maintain its own load serving obligations as a balancing authority”). However, in its Business Practice Manual for Operations, the penalty parameter for the “Tagged Quantity for exports” is 3100, whereas load is 1450. Further, per the excerpt from CAISO’s BPM for Market Operations shown below, it appears that tagged exports have higher priority than load in real time. It would be helpful for CAISO to explain this potential discrepancy, and how CAISO’s proposal to cut firm-provisional exports in real-time will work in conjunction with real time market penalty parameters in its software.

Real Time Market Parameters

|

Penalty Price Description

|

Scheduling Run Value Based on $1000 Cap

|

Pricing Run Value Based on $1000 Cap

|

Scheduling Run Value Based on $2000 Cap

|

Pricing Run Value Based on $2000 Cap

|

Comment

|

|

Energy balance/Load curtailment, RUC cleared self-scheduled export using identified non-RA capacity.

RUC cleared export leg of a wheel through self-schedule.

Real-time market self-scheduled export using identified non-RA capacity.

Real-time export leg of a wheel through self-schedule.

|

1450

|

1000

|

2900

|

2000

|

Scheduling run penalty price is set high to achieve high priority in serving forecast load and exports that utilize non-RA capacity. Energy bid cap as pricing run parameter reflects energy supply shortage.

|

Second, in its straw proposal, CAISO indicates that it plans to support firm-provisional exports “to the extent contingency reserves have been deployed and were unable to be recovered, or an event outside of existing planning criteria occurs wherein the CAISO is unable to meet its internal demand through the exercise of its reserves.” It would be helpful for CAISO to provide more detail on what resources it is referring to, which would be supporting these lower priority “firm-provisional” exports before curtailing them, since there are a variety of different contingencies and reserves that can be called in different time horizons. One example is that it is CPUC staff’s understanding that if CAISO were using its reserves, this would mean that it would be calling on its RDRR and arming load, and that this would be done to support these firm-provisional exports. It would be helpful for CAISO to clarify if this understanding is correct and, if not, the order of operations that CAISO expects that it will deploy during these types of stressed system conditions.

Third, CAISO also indicates that its default would be to not curtail exports to a BAA in an EEA-2 (“with the default being to exclude curtailments into BAAs that have entered into an EEA-2”). On the other hand, the only time CAISO will cut exports appears to be only after it has deploying RDRR and armed load in order to support exports, which suggests that the only circumstances under which CAISO will cut exports is when CAISO itself is in an EEA-2. It would be helpful for CAISO to clarify if this is correct and if not, why not. In addition, this raises the question – would CAISO curtail exports to a BAA that is in an EEA-2 if the CAISO BAA itself is also in an EEA-2, which seems inevitable if CAISO is at the point of cutting exports in the first place?

Further, during the last EDAM RSE stakeholder meeting, one EIM entity clarified that it has agreements with other Western BAAs to provide assistance for forced outages, but it would not provide this assistance to a BAA for imports that failed to deliver. It would be helpful for CAISO to clarify why it should, as a BAA, support exports when the underlying imports that cleared exports for that transaction failed to deliver, if other EIM entities are indicating they would not do the equivalent, and why California customers should bear this potential reliability risk (e.g., potentially driving itself into an EEA-2 by deploying RDRR and arming load to support provisionally firm exports, with the attendant scarcity pricing and reliability risks associated with such actions) if other EIM entities are not prepared to do so as well.

- CPUC staff is interested in learning more about CAISO’s proposal to allow WEIM entities that fail the RSE, to cure the resource insufficiency through a hurdle rate priced at the bid cap (i.e., either $1,000/MWh or $2,000/MWh, depending on cost verified bids above the soft bid cap).

First, CPUC staff requests that CAISO clarify if RDRR will be activated and deployed (and counted in the RSE) before relying on this type of emergency assistance and strongly urges CAISO to ensure that RDRR (and BIP in particular) are counted in the RSE to ensure that CAISO does not fail the RSE and that RDRR is in fact deployed before using such emergency assistance.

CPUC staff’s understanding of how RDRR (and BIP in particular) rests on language in the settlement agreement, signed by parties and approved by the CPUC in D.10-06-034,[3] which explicitly indicates that RDRR is to be deployed to “help mitigate, or limit the duration of, [s]carcity [p]ricing events” and “immediately prior to the CAISO need to canvas neighboring balancing authorities and other entities for available exceptional dispatch energy/capacity” (see language below).

Thus, to the extent that the CAISO’s proposal is a form of scarcity pricing and emergency assistance from other BAAs at the bid cap, it follows that the RDRR programs should be activated to be included in the RSE and called before using emergency assistance from neighboring balancing authorities. Since this was not discussed in the issue paper, CPUC staff request clarification on how CAISO proposes to incorporate the RDRR program to ensure that CAISO does not unnecessarily fail the RSE, effectuate scarcity pricing and rely on other balancing authorities for power at the bid cap before activating and dispatching the RDRR programs.

In addition, CPUC staff requests clarification on how this program would work in practice. Would the scarcity prices clear the entire FMM and RTD or would these prices apply just to the EIM transfers necessary for emergency assistance?

- CPUC staff continues to believe that the T-40 transmission tagging requirement imposed on CAISO alone (in the RSE) is discriminatory and recommends that either CAISO remove it, impose it on all WEIM entities, or develop an intertie uncertainty adder applicable to CAISO and other WEIM entities on non-discriminatory basis.

In its straw proposal, CAISO proposes to permanently remove the intertie uncertainty adder from the capacity test. In addition, CAISO indicates that “given the recent changes to require the transmission profile of an e-tag for an import to the CAISO BAA to count in the WEIM RSE, all intertie transactions used to pass the WEIM RSE have similar expectations of delivery, equally situating all parties regarding potential for intertie uncertainty to arise.”

CPUC staff requests that CAISO explain how all intertie transactions used to pass the WEIM RSE have similar expectations of delivery and how all parties are equally situated. From CPUC staff’s perspective, the T-40 transmission tagging requirement is included in the RSE only for the CAISO balancing authority and not for the other BAAs. Further, CPUC staff request that CAISO explain how the other balancing authorities are situated – do they have a T-40 transmission tagging requirement, and if not, what requirement do they have that is similar?

Further, CPUC staff still do not understand how this does not treat similarly situated entities differently. For example, assume that the CAISO and another CA EIM entity have an import contract with the same entity in the NW, but the transmission line fails at T-45. In this case, the CAISO imports would be removed from the RSE if load serving entity was not able to obtain a transmission tag by T-40 (a CAISO-specific requirement), but the other California entity would not need to show the import failure because e-tags are only required at T-20 (which we understand to be a WECC requirement). CPUC staff would appreciate CAISO staff explaining how these entities are not being treated differently for purposes of the RSE.

In addition, CPUC staff agrees with CAISO that it should develop a more granular process to allocate the costs associated with RSE failure and emergency assistance, and staff encourages CAISO to address this in this stakeholder process.

Finally, it would be helpful for CAISO to provide further data on historic CAISO T-40 transmission tagging failures. What portion of these failures are for RA resources? What portion of these failures are for day-ahead cleared imports? What portion of these failures are for HASP cleared imports? If the failure is primarily for HASP cleared imports that are clearing export transfers, how would the transmission tag failures affect the RSE (given that non-supported exports are no longer going to be included). and how will these HASP transmission tag failures affect reliability for CAISO customers (given that they would need to support firm-provisional exports up until deployment of RDRR and arming load)?

In addition, information on the extent to which imports fail to tag by T-40 – and under what conditions – will also allow CAISO and parties to determine whether CAISO needs to consider changes to its penalty for intertie deviations and whether this issue should be further examined as part of this initiative.

[1] For example, assume CAISO has balanced load and resources at 40,000 MW (excluding consideration of reserve requirements), and 1,000 MW of expected WEIM transfers and, as a result, clears 1,000 MW of exports. While CAISO is resource sufficient in this instance, with 40,000 MW of load and 40,000 MW of resources, it would fail the RSE because it would have only 40,000 MW of resources but 41,000 MW of load and exports to support.

[2] “The CAISO proposes to only count high priority block hourly export transfers and lower priority block hourly transfers that it has a reasonable expectation were sourced from its control area in the net scheduled interchange that is used to inform its WEIM RSE obligation.”

[3] In addition, D.18-11-029, clarified that RDRR was supposed to be called at a warning, not during an emergency, but before, which argues for inclusion in the RSE test itself, should CAISO anticipate failing the test.